Of special importance, the combination of helicopter parenting, fears for children’s safety, and the allure of screens means that members of iGen spend much less time than previous generations did going out with friends while unsupervised by an adult. The bottom line is that when members of iGen arrived on campus, beginning in the fall of 2013, they had accumulated less unsupervised time and fewer offline life experiences than had any previous generation. As Twenge puts it, “18-year-olds now act like 15-year-olds used to, and 13-year-olds like 10-year-olds. Teens are physically safer than ever, yet they are more mentally vulnerable.” Most of these trends are showing up across social classes, races, and ethnicities. Members of iGen, therefore, may not (on average) be as ready for college as were eighteen-year-olds of previous generations. This might explain why college students are suddenly asking for more protection and adult intervention in their affairs and interpersonal conflicts. The second major generational change is a rapid rise in rates of anxiety and depression. We created three graphs below using the same data that Twenge reports in iGen. The graphs are straightforward and tell a shocking story.

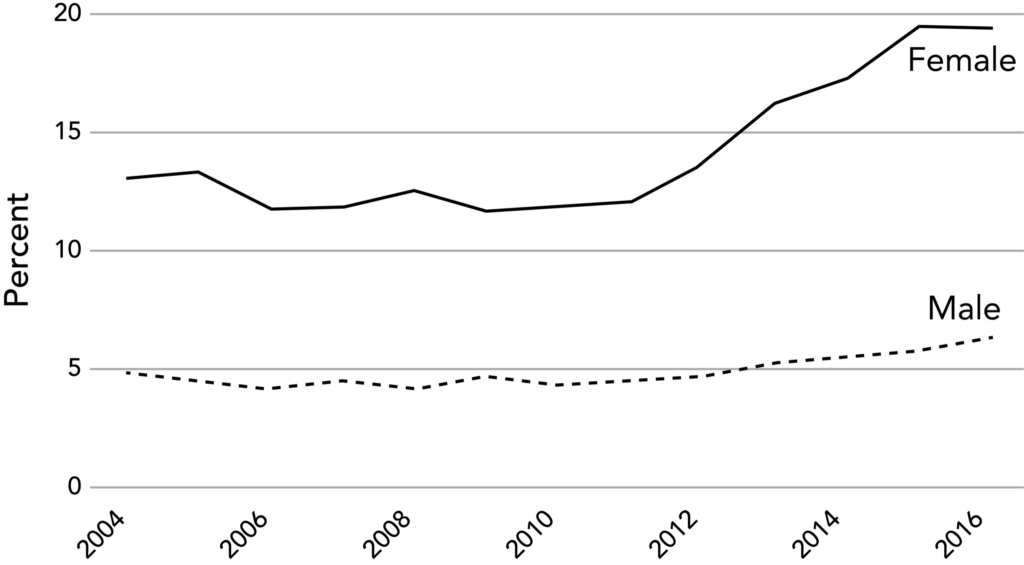

Studies of mental illness have long shown that girls have higher rates of depression and anxiety than boys do. The differences are small or nonexistent before puberty, but they increase at the start of puberty. The gap between adolescent girls and boys was fairly steady in the early 2000s, but beginning around 2011, it widened as the rate for girls grew rapidly. By 2016, as you can see in Figure 7.1, roughly one out of every five girls reported symptoms that met the criteria for having experienced a major depressive episode in the previous year. The rate for boys went up, too, but more slowly (from 4.5% in 2011 to 6.4% in 2016). Have things really changed so much for teenagers just in the last seven years? Maybe Figure 7.1 merely reflects changes in diagnostic criteria? Perhaps the bar has been lowered for giving out diagnoses of depression, and maybe that’s a good thing, if more people now get help? Perhaps, but lowering the bar for diagnosis and encouraging more people to use the language of therapy and mental illness are likely to have some negative effects, too. Applying labels to people can create what is called a looping effect: it can change the behavior of the person being labeled and become a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is part of why labeling is such a powerful cognitive distortion. If depression becomes part of your identity, then over time you’ll develop corresponding schemas about yourself and your prospects (I’m no good and my future is hopeless). These schemas will make it harder for you to marshal the energy and focus to take on challenges that, if you were to master them, would weaken the grip of depression. We are not denying the reality of depression. We would never tell depressed people to just “toughen up” and get over it—Greg knows firsthand how unhelpful that would be. Rather, we are saying that lowering the bar (or encouraging “concept creep”) in applying mental health labels may increase the number of people who suffer.

Depression rates and mental disorders in teenagers have increased. In this book, the author(s) speculate, based on the correlation, that a lot of this increase can be attributed to both helicopter parenting + the increase in use of mobile devices for our children. The lack of unsupervised experiences when young might cause a generation to be unprepared and inadequate when dealing with the social issues when they get into college and the workforce.